Private: Media and conflict

April 21, 2025

The Scope of International Law Protections for Journalists

April 21, 2025April 21, 2025 – Source: Mission Local –

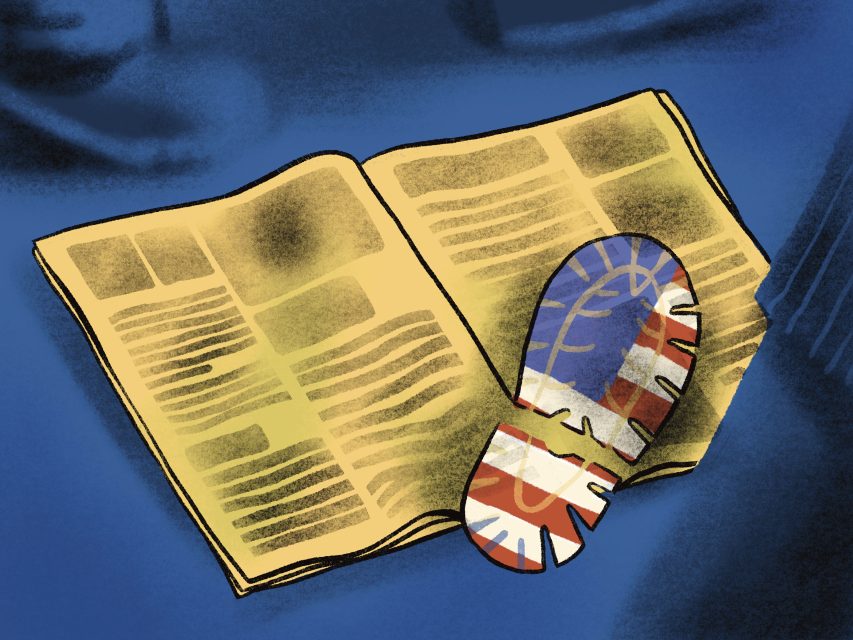

In the last month, Luz Mely Reyes, a reporter at the International Center for Journalists, has been advised to avoid international travel, close her social media account, and scrub information from her phone. It’s the same advice that she used to follow before she moved to the United States in 2020 — back in the days when she was living in her home country of Venezuela, covering human rights and politics.

Now, it’s becoming the new normal Stateside. “Some people are very worried about the consequences of speaking up and having a dissident approach to the government,” Reyes said. “The self-censorship is taking form.”

Reyes and other foreign journalists have long described the United States as “a beacon of hope.” They left their homes in pursuit of working in a country that values freedom of the press.

That America might be in the past, they fear.

“Before, I wouldn’t have thought twice about pitching a story that is about, for instance, student visas being revoked in colleges,” said another foreign journalist living in California. Now, she is hesitant. “It hits a little bit too close to what I’m most afraid of.”

She has stopped posting on social media, and turned down invitations to speak at public forums. “It’s so ridiculous. Journalists usually want more attention to your work,” she said. “Right now, I want less attention.”

In recent weeks, journalists from countries with stringent restrictions on the press, are now asking themselves: Self-censor, or risk being kicked out of the United States?

The danger is genuine. President Donald Trump has doubled down on immigration enforcement and revoked over 1,300 student visas, sometimes for no apparent reason. Some journalists said they have begun circumscribing their work as a precaution — refraining from pitching stories that might draw the attention of the current administration, and weighing whether to remove their bylines from articles in their archive.

It’s a worry that James Wheaton, a law lecturer at UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, has been hearing frequently from international journalism students — three different ones approached him with the same concerns in just one week, Wheaton said. They can’t go home because it’s not safe for them as journalists, they told him. “But the U.S. is starting to feel exactly like their home country.”

Those fears aren’t unreasonable. As of April 16, more than 1,300 student visas have been revoked without warning, including at least 23 at U.C. Berkeley and six at Stanford University, according to a tally by Inside Higher Ed.

With a student visa, an international journalist can be a full-time student or work legally in the United States for up to three years after graduation. When the visa is revoked and the student’s record in a government system is terminated, their legal status ends and they are at risk of deportation unless they file for reinstatement, typically within five months.

The visa revocations seem to be escalating. In March, Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that the administration had revoked 300 student visas because of pro-Palestinian activism. That number has more than quadrupled.

On March 25, Rumeysa Ozturk, a Ph.D student at Tufts University, was arrested by plainclothes ICE officers while walking to dinner. She was targeted because of an op-ed in the school newspaper that she had co-written with three other students, criticizing the university’s response to the Israel-Gaza war.

Ozturk’s arrest was particularly unsettling to international journalists. “It’s a déjà vu moment,” said a U.S.-based journalist from India, who spoke on condition of anonymity due to their own immigration concerns. “The main reason journalists in exile choose to come here is because they have a voice.” The spaces where they can use that voice, they said, “is getting smaller and smaller.”

“In the current climate, there’s lack of any protection if you’re on a visa,” said the Indian journalist. “If you’re an international journalist, the risk is even higher.”

When crossing the border, visa holders have minimal rights, compared to permanent residents or citizens. In the past month, visa holders have been arrested by immigration officers, even without committing any crime.

In preparation for a trip back to his home country, another foreign journalist deleted his tweets on X, memorized an immigration hotline number, and considered getting a burner phone to cross the border.

“There’s no rules anymore,” said the journalist based in the Bay Area. “And it is scary.”

Wheaton, the law professor, cautions students against changing their behavior by looking for patterns or rationales for the visa revocations. “There aren’t any,” Wheaton said.

“The cruelty is the point. The uncertainty is the point,” he continued. “It’s completely arbitrary.” The goal of this uncertainty, Wheaton adds, is to make people afraid. “You start not doing things, and that’s what they want. If you’re not going to leave, they at least want you to shut up. Because the strongest form of censorship is self-censorship.”

Clayton Weimers, executive director at the U.S. office of Reporters Without Borders, agrees. The United States may not be in a place where censorship is as extreme as it is in Russia and China, Weimers said, but he has noticed commonalities with places like Hungary or Turkey, which “had democratic institutions that were systematically weakened by leaders who dismantled them.”

“One of the places they started was with the media,” Weimers said, of that dismantling. “It was forcing the media into obedience over the kind of language they use, the kind of stories they covered and really shrinking the space for what it was possible to say.”

“Outside the United States, very often when you are critical of powerful people, it’s easy to use that criticism as an excuse to punish you,” added the Bay Area based journalist.

The current situation in the United States, he said, makes people afraid to criticize the current administration. “Now people think that if you have an opinion that goes against what the administration believes in, that is due grounds for you to be kicked out of the country,” he said. “That seems — I hate to use this term lightly — very fascist.”

Many U.S. citizens might not realize how risky this situation is, said Reyes, the Venezuelan journalist, because they’ve never experienced anything like this before. “They don’t realize the danger. Because I think they overestimate the health of the system.”

“It’s not only the situation about media, about journalism, about targeting migrants, it’s about dissidents,” Reyes said. “If you are in a country where the dissidents are pointed as an enemy, you have to pay attention.”

Mission Local employs four foreign journalists, including the author of this piece, who is withholding their byline in fear of immigration consequences.

To journalists from repressive countries, the U.S. is feeling more and more like home