“Do you see that guy taking pictures of us?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t stare. He’s following us.”

We were in Bucharest’s Old Town in the spring of 2023, returning from a meeting with a source for a story about the Tate brothers and their alleged connections to Romanian organized crime.

Luiza, my partner in life and journalism, stopped to grab some fries from a takeaway shop, while I, an investigative reporter trained in anti-surveillance techniques, continued on to the RISE Project newsroom, where we were working at the time, to pick up my phone and laptop.

When I came back down, I noticed a man wearing a headset. Startled, he realized I’d seen him, and he quickly tried to change direction. I’ve learned in journalist safety training sessions to spot unusual behavior, so I discreetly took a few photos of him.

We were already on high alert. A few days earlier, I had gone to the Court of Appeal to meet Costel Corduneanu, a prominent leader of one of Romania’s infamous organized crime groups, who died recently.

I was trying to interview Corduneanu about a huge money-laundering scheme in which connections to British-American influencer Andrew Tate had emerged. Our investigative series about Tate’s criminal history in Romania and the women he exploited for money, fame and Ferraris, had unfolded in ways that we had not anticipated, reaching deep into the heart of the largest mafia syndicate in post-Communist Romania.

I headed back towards where Luiza and I had agreed to meet, but a misunderstanding over the phone had us taking different streets. As I doubled back, I noticed another man wearing a headset. He changed direction at the same time I did, so I stopped and pretended to listen to a busker playing the violin in front of the National Bank. The man with the headset stopped too. I pretended to photograph the musician, but managed to capture the other man in the shot as well.

So, there were two of them with headsets, which I figured meant they were being coordinated from an office – and they were likely not alone. We would later learn that six people in all were tailing us.

I finally met up with Luiza and showed her the photo of the man in the headset. She was alarmed too. It was clear we were being watched.

In the official documents of the state law enforcement agency used to surveil us, which we were able to view a year later, the people following us noted:

“At the intersection with Smârdan Street, they suddenly stopped and began carefully observing the area, with Ilie Victor using his mobile phone for recording or photographing. Considering the atypical and unusual behaviour of the two, it was decided to temporarily suspend the surveillance.”

We quickened our pace towards the metro and didn’t look back. We needed to pick up our child from daycare. Luiza went up to the rented apartment where we live and watched behind me to see if anyone was still following. There was.

When I arrived at the daycare centre, I grabbed our child by the hand and took the fastest route home, sticking to areas covered by public and private surveillance cameras and heavy foot traffic. Once home, we used every lock on the door.

According to the documents subsequently provided to us by the law enforcement agency monitoring us, we now know that the surveillance operation continued the following day:

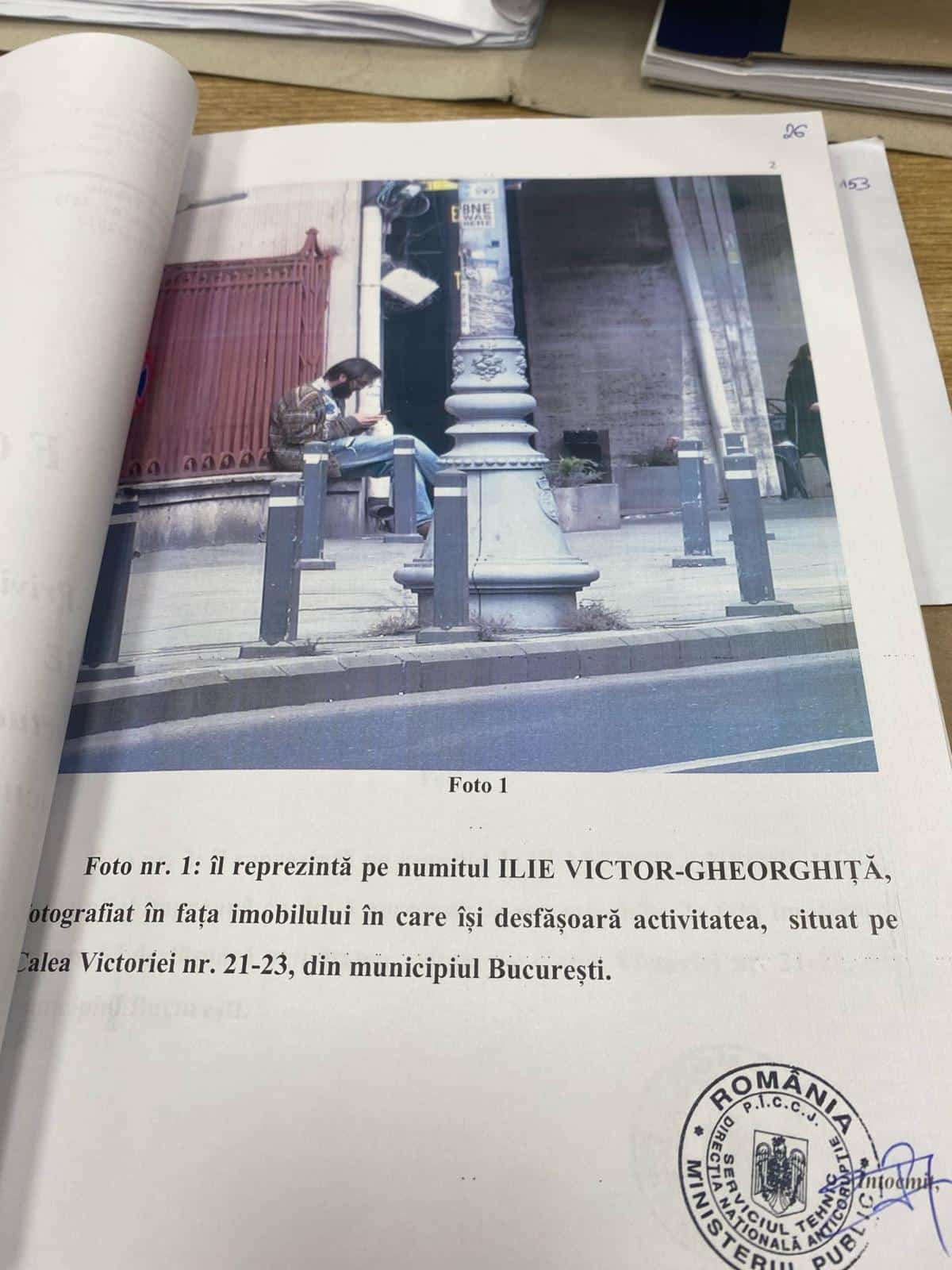

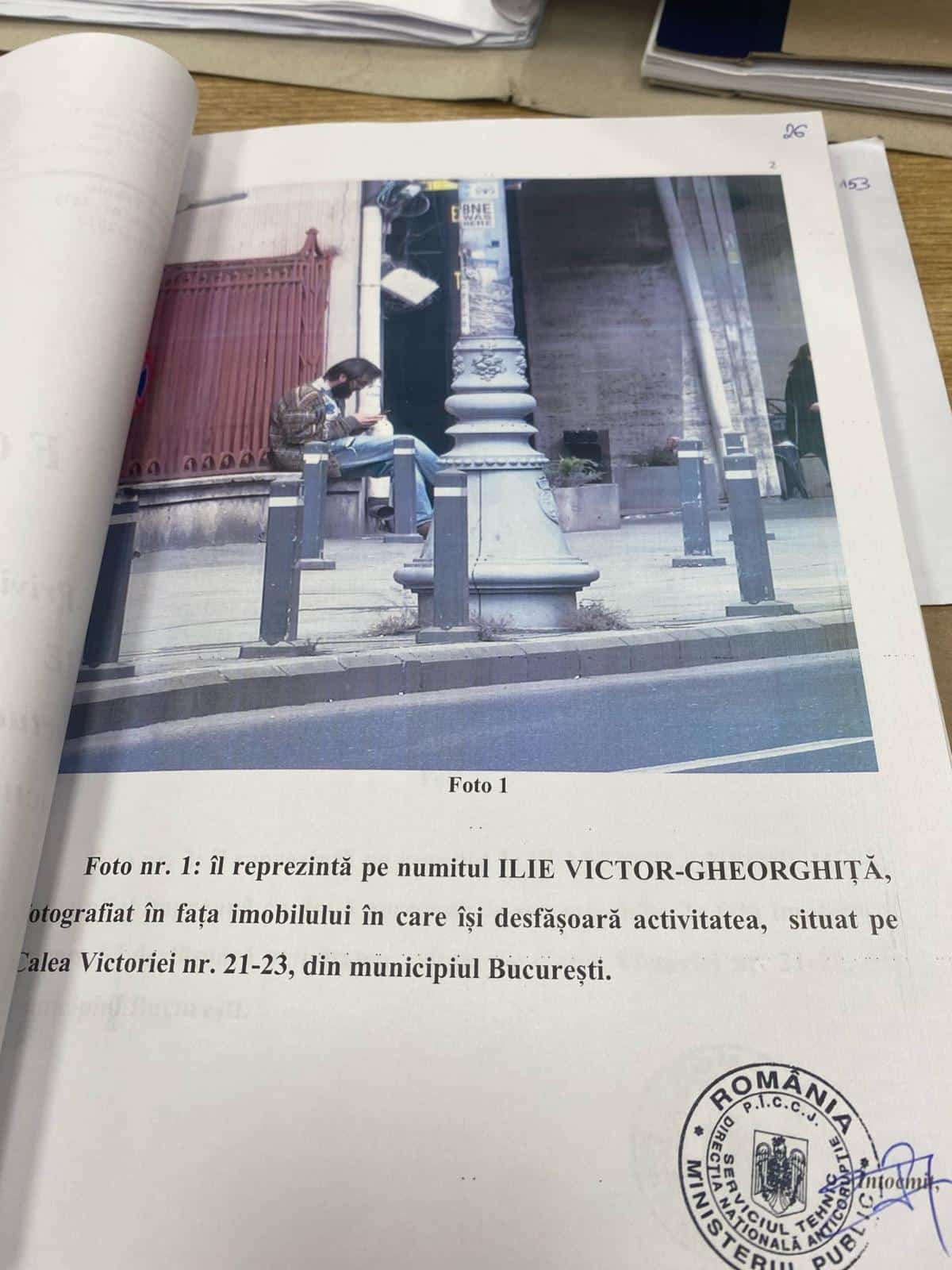

“Photo no. 1: depicts the individual named Ilie Victor, photographed in front of the building where he carries out his activity, located at 21-23 Calea Victoriei, in Bucharest.”

The location being referred to is the RISE Project newsroom, for years the most prominent investigative media outlet in Romania.

I spotted the same man who I had managed to startle the previous day sitting on the café terrace downstairs. There was another man sitting at the table with him. A grey 4×4 was parked by the curb, where it remained the whole day. In the afternoon, when we left again to pick up our child, the car sped off, while in the metro station we spotted more suspicious individuals. We could no longer tell what was real and what was just in our heads.

The following day, a source behind one of my investigations insisted on meeting face to face in order to hand over a new cache of encrypted data. I took a convoluted route to make sure I’d notice if anyone was following me. But what I didn’t take into account was the phone in my pocket.

Without being aware of it at the time, I was actually in the second week of technical surveillance and under a provisional ordinance for physical and environmental recordings. Though no incoming calls appeared on my screen, my phone was being dialled by the Technical Service of the National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA) as I headed to meet the source. The phone sent signals to the nearest relay.

Documents from DNA Iasi – the institution I would learn six months later had opened a case against me for incitement to abuse and bribery – stated that the street surveillance lasted 48 hours. That was enough for DNA, and by extension the Romanian state, to identify two of the sources that we met over those three days that I have recounted.

Liana Ganea, president of ActiveWatch, a Romanian NGO that defends press freedom, says the case is “shocking” and “we see just how easily a prosecutor can place a journalist under surveillance.”

Ganea explains that “surveillance warrants against journalists are not just a violation of an individual’s right to privacy; they represent an infringement on a professional right: the protection of journalistic sources.”

Moreover, she adds, “we cannot help but ask, with deep concern, how many similar cases of journalist surveillance in Romania have occurred without ever coming to public attention. These abuses by law enforcement agencies add to a long list of systemic pressures in Romania: prosecutors, police officers and judges coercing journalists to reveal their sources; unlawful confiscation and forensic searches of journalistic equipment; the opening of criminal cases and summoning of journalists for interrogation over blatantly unfounded complaints – often used as a pretext for public smear campaigns; and the inaction or outright obstruction of investigations into crimes targeting journalists.”

The surveillance of my phone, according to the same documents, lasted two months and represented another potential abuse, as confirmed by several police officers and prosecutors. However, in Iasi, a town in northern Romania, the intimidation and surveillance of journalists by state institutions, those meant to protect them from the criminals they write about, have become deeply ingrained practices.

What sent DNA Iasi into battle

In my case, it all started with an undercover operation – a legitimate journalistic research method used when all other avenues to expose illegality have been exhausted.

I had previously employed such a practice in 2022, for example, when making the documentary The Clan of the Great White, published by Recorder, where I uncovered the Romanian Orthodox Church’s enthusiasm for doing business deals involving public funds, as well as last year for the investigative program “Dispatches” on Channel 4 in the UK.

In February 2023, the RISE Project and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) were investigating the grain trade from Ukraine through Romania. Our colleagues had learned from several sources that in Iasi – a city close to the border – there was a key figure, Gabriel Ciobanu, head of the Directorate for Veterinary Health and Food Safety (DSVSA) in Iasi for 16 years, who was enabling smuggled Ukrainian grain to enter Romania using shell companies in exchange for bribes.

I called Ciobanu, pretending to be a businessman seeking a meeting with the head of the DSVSA, and he invited us to a meeting to discuss matters further.

Ciobanu welcomed me into his office, asked me to leave my phone there, and led me into another room. I told him I had 50 trucks of cereals from the Ukrainian front lines and that all I needed from him was a company to handle the import paperwork on our end. He agreed but said he needed a week to arrange the deal.

I wrote “10,000” on a small piece of paper – the euro amount our sources had told us he expected in exchange for the favour. He agreed to that as well, but said we’d discuss money after sealing the deal. I left and stopped the recording.

A few days later, in the complaint he filed with the General Anti-Corruption Directorate (DGA) in Iasi, Ciobanu claimed that someone had just tried to bribe him. According to him, it was that individual who had suggested leaving the phones behind and moving to another room. He also claimed that he was horrified, not pleased, by the note with “10,000” written on it.

The DGA forwarded the case to the National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA), and the Iasi branch of DNA opened a criminal case for incitement to abuse of office and bribery.

I subsequently found out in September 2023, half a year after we discovered that we were being followed in Bucharest, that DNA Iasi had been listening to my conversations for two months and sent six undercover surveillance officers from the Technical Service of DNA Bucharest to tail us for 48 hours.

I discovered this when a DNA Iasi officer called me to testify in the case that the prosecutor was preparing to close due to a lack of evidence proving that I had had the intention to commit any crimes. (Romanian law stipulates that any citizen who has been subject to surveillance needs to be informed of any violation to their privacy once the official investigation is closed.)

That same officer told me that DNA Iasi had identified me right away. The anti-corruption investigators knew I was an investigative journalist, and it would have been straightforward to find out that I had done undercover work before, at the RISE Project and Recorder. Yet they chose to use Ciobanu’s complaint as a pretext to monitor me rather than investigate what was really happening at DSVSA Iasi.

In doing so, the investigators learned of my sources, my work topics, my routes, my network and my conversations. After a month of surveillance, they obtained a warrant to extend the surveillance by another month, justifying it on my “suspicious behavior”, which was, of course, solely down to the realization that I was being followed.

Due to the complicated judicial procedures, it wasn’t until the spring of 2024 that we were able to obtain the first documents from the surveillance case launched by DNA Iasi.

We spoke with over 20 police officers, prosecutors, judges, intelligence officers and human rights activists to understand DNA Iasi’s legal approach. Their verdict was unanimous: opening such a criminal case against a journalist is not in itself illegal, but the surveillance and extension of monitoring are at least unethical and dangerous for freedom of expression in a democracy.

Not alone

Worryingly, I am far from alone in having found myself the subject of malicious surveillance by DNA Iasi.

In Iasi, a small group of investigative journalists has tirelessly reported on the activities of Mayor Mihai Chirica’s inner circle and organized crime in the city’s real estate sector. They’ve exposed the complicity that has disfigured the city’s landscape at the expense of its citizens. This work has made these journalists targets of threats and intimidation from both mobsters and public officials alike. They also ended up being the subjects of several surveillance warrants issued by DNA Iasi and other local law enforcement agencies.

“This was the way the game was played in Iasi during the golden age of the real estate mafia,” says Rares Neamtu, a journalist with 7 Iasi, a local independent media outlet.

Neamtu and his colleagues, Tudor Leahu and Andrei Viliche, are veteran reporters. Together, they have published dozens of investigations about the corruption in the city hall that was led by Chirica and his then-deputy, Gabriel Harabagiu. In 2017, the reporters were subjected to surveillance by DNA Iasi that was a potential abuse of the system.

In December 2017, the three journalists were working on a series of investigations into the city’s then-chief architect and deputy mayor Harabagiu. The officials were becoming increasingly wealthy at the expense of the public budget and the environment, by approving illegal construction in protected areas. According to Neamtu and his colleagues, all of this happened with Mayor Chirica’s approval, but on the say-so of the deputy mayor’s signature.

Prosecutors opened a case based on their revelations, but as well as investigating the alleged corruption in City Hall, they also began looking into the alleged harassment of the city officials by journalists looking to gain access to public information. Yet while the corruption cases against the mayor and deputy mayor were eventually dropped, surveillance of the journalists continued for two more months on the pretext of suspicions of harassment, blackmail and threats.

The public officials were not wiretapped – only the journalists were. To extend the wiretapping warrants, as DNA Iasi needed documentation to justify continuing the investigation, Deputy Mayor Harabagiu himself filed a complaint, the journalists subsequently discovered:

“I request an investigation into and verification of the methods through which these reporters gain access to documents related to the proper functioning of a public institution, by taking photocopies without the written consent of the respective institution.”

The deputy mayor also stated to DNA Iasi that journalists’ access to public-interest information constituted “possible interference in his activities”.

“From the very beginning, the authorities acted maliciously, starting with the decision to initiate this case. They focused on the so-called ‘blackmail’ we allegedly practiced to obtain public-interest information, rather than on the information we published – namely, the bribes received by the city hall’s chief architect from a real estate developer,” explains Neamtu, referring to how their investigations exposed multiple offences committed by public officials.

The journalists found out about the case against them almost two years later, when it was transferred to another prosecutor, who decided to inform them that they had been under surveillance before the investigation was closed. They weren’t allowed to see when or where they were surveilled – only to read transcripts of certain phone conversations.

“There were over 50 DVDs with recordings!” exclaims Leahu.

“Basically, their [DNA Iasi] approach was, ‘Let’s just wiretap them – we’ll catch them in the end; they must be up to something, and we’ll nail them soon enough’,” says Neamtu.

But the investigators found nothing. So, an associate of the deputy mayor, Mircea Rotariu, started vandalizing the journalists’ cars with feces and sending death threats by phone. “He went to Tudor’s home, started banging on the door, and scared his children. Then he sent him a message saying, ‘Why did your girls get scared’?” Neamtu continues.

The journalists gathered evidence and went to the police to file a complaint. A police officer opened a criminal case but did barely anything with it. Years later, they were informed that the offences had indeed occurred, the case was sent to court, but in the meantime the statute of limitations had expired.

Despite the harassment, the journalists refused to be intimidated and continued to report on the network of public officials and organized crime profiting from real estate deals in Iasi. This earned them another criminal case and yet another round of wiretapping.

In 2020, the journalists for 7 Iasi began working on a story about a new real estate heist in Iasi. This time, “the person who filed the blackmail complaint against us was the one supplying lawn services to Iasi City Hall,” Neamtu recalls.

The journalists insist they had never met the businessman, let alone asked him for money to stop writing about him. The case ended up with the same police officer who had previously allowed the threats against the journalists to become time-barred. In the alleged blackmail case, however, he was much more zealous, wiretapping the journalists for three months. Subsequently, he was promoted to DNA Iasi from being a serving police officer, according to Leahu and Neamtu.

The Iasi office of DNA is now led by prosecutor Cristina Chiriac. Chiriac gained notoriety following revelations from a national investigative outlet, SaFieLumina.ro, about sexual abuse committed by the bishop of Husi. Journalists showed that Chiriac, then a prosecutor, had kept incriminating video evidence of the bishop’s abuse locked away in her desk drawer for years, instead investigating the victim for blackmail.

Neamtu believes that “the prosecutors, working hand in hand with the local authorities, were trying to uncover who our sources were and where the money came from – who was helping us financially to stay alive.” He discovered from the criminal case files that even clients advertising on the 7 Iasi website were called in to submit complaints.

That second DNA Iasi case against the journalists was closed, too, due to a lack of evidence. But the fight continued on other fronts. “The mayor and his mob fired my wife from her job – she worked for a company owned by [Iasi] City Hall,” Neamtu recalls.

Things weren’t any easier for his colleague. Leahu remembers how, in 2020, a complaint was filed against him with Iasi social services: “It claimed I was a drug addict and an alcoholic who couldn’t take care of my kids. Both I and my children were investigated. My wife and I were summoned for interrogations by social services, as were the kids – separately. They conducted all sorts of checks, the kind they do in alleged abuse cases, until they finally concluded that my children were not victims of any abuse, that they were growing up in a normal family environment, and that they were excelling in school.”

“We’ve become hardened,” the journalists explain when asked how they manage to keep going. “But it’s infuriating that nothing changes and there’s no protection for journalists whatsoever. The only difference between this and what happens in Russia is that there, they’ll throw you out of a window – otherwise, the methods are the same,” Leahu says.

“I’ll end up writing on a sheet of paper,” he concludes bitterly.

Russia also comes to mind for Gabriel Gachi, a journalist with nearly 30 years of experience. He now leads Reporter IS, a news and investigative publication which systematically exposes abuses in Iasi’s institutions and corruption that’s draining local budgets.

“I’ll either end up in prison or be discredited – just like in Russia,” Gachi says, disheartened.

Both his sources and those of the reporters at 7 Iasi warn that they may be the targets of a new criminal case – this time, together.

Recently, several advertisers with Reporter IS and 7 Iasi were allegedly asked by DIICOT, the anti-mafia prosecutors, whether they had ever been blackmailed by journalists exposing corruption in City Hall to sign advertising contracts. Neither Gachi, Leahu nor any of their colleagues were officially notified that a criminal investigation had been launched against them.

“We don’t know anything– it’s all speculation at this stage. But we’re probably under surveillance,” Gachi believes.

Gachi, too, has received death threats from the same people who threatened the 7 Iasi reporters and had to clean up human waste dumped at his newsroom. The reporter filed a complaint. Nothing happened, he says.

“In Iasi, just like in other [Romanian] counties, the police operate as a political-financial octopus,” Gachi explains.

It’s clear to him that the people they report on are using every possible method to discredit them. “The thing is, we just continue to do our job. We don’t beg, we don’t ask for favors – we simply do our job,” Gachi sighs. “But I am worried. It’s something that gnaws at me.”

Meanwhile, criminal cases are piling up against Mayor Chirica and his circle for alleged corruption and membership of organized crime groups – the very same offences that local journalists like Gachi and Leahu have exposed, but which are taking years for prosecutors to officially investigate.